Some of the Greek gods were immortal, but others were not. Immortality was not a prerequisite for the gods. Based on the currently popular religions we assume that being a god meant omnipotent and immortal, but the polytheism of earlier religions distinguished between “immortal” or “undying” gods and “dying and resurrected” gods, often also referred to as the Son of God.

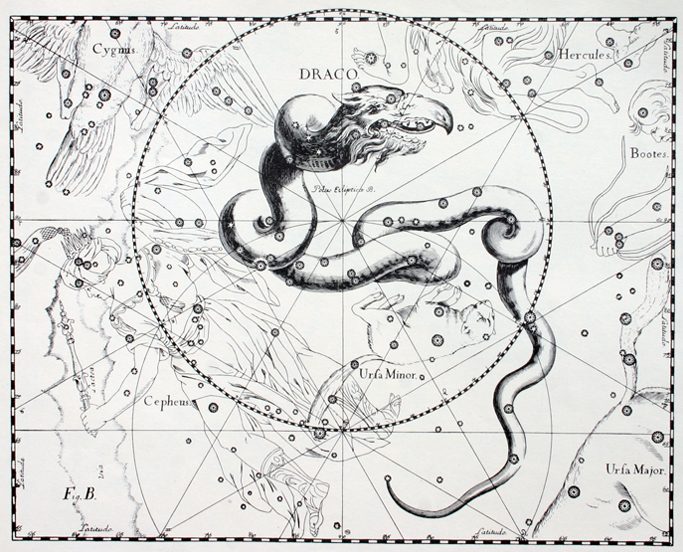

Sir James Frazer discussed the ubiquity, and common patterns of dying and resurrected gods across numerous cultures and eras in his twelve volume opus on myth, magic and superstition: The Golden Bough. Sir Frazer equated the life, death, and rebirth of these gods to the cycles of growth, reaping, and sowing new seed in the production of grain. I was perplexed that an annual agricultural cycle could result in so many different times for the death and rebirth of gods across these cultures. It was only when I read a reference to the “highest seat of heaven” in the North Polar region, as the place where heroes go to become immortal, that it dawned on me that the immortality was a description of circumpolar stars, which never set. Since the ancients equated the horizon with the edge of the Underworld, those stars which did not disappear below the horizon were dubbed immortal.

This distinction also sheds new light on the “dying and resurrected” gods. Those key stars which are found closer to the celestial equator disappear for days or even months at a time as the sun crosses that part of the sky. In other words, while the sun is conjunct any star it will pass overhead invisible in the scattered daylight. Once the sun separates from that part of the sky, the star will reappear on the eastern horizon at predawn. Festivals celebrated the rebirth of the god timed to the helical rising of his star. Since different cults and groups followed different god/stars, the death (falling below the horizon) and rebirth (helical rising) occurred throughout the year, rather than being in relation to the solar cycle.