The sacred marriage of the gods was not integral to the relationship of the Greek religion to the stars, but the rules of that ancient ritual crop up in many of the myths that describe the astronomical events, so it is helpful to understand this framework for Greek religion. By the time that myths were recorded in writing, the patriarchy was firmly established and most stories no longer dwelled on the salient aspects of the hieros gamos or sacred marriage, because it hailed from a time when women held more spiritual power.

The basic principle of the hieros gamos is that the fertility of the land is dependent upon good, fertile sex among the gods. Since early peoples believed in sympathetic magic, the high priestess was considered a manifestation of the Great Goddess and she chose a partner, often through a ritual contest, who was the “son of god” with whom she modeled abundant, joyful sex. The earliest versions of this ritual predated Greek civilization and probably remained as an undercurrent in Greek myths that were retained and expressed in agricultural abundance rites. At one time the priestess may have chosen a new partner every year to ensure his virility. Later her consort may have been retained as long as he was virile and the crops were good or if he retained her favor. Should celestial or agricultural omens or simply just the favor of the high priestess wane, the consort/sacred king would be ritually sacrificed and his blood and body parts were scattered across the land as magic fertilizer.

In some rituals new contestants would fight and kill the sacred king, in other myths the candidate witnessed the goddess arising from her bath and judging from his erection would either be chosen as consort or killed for his impudence. The old king was commonly referred to as the “father” and the incoming consort as the “son of god”, because they were the embodiment of generations of the same god, even though they had no blood relation. One of the benefits of becoming sacred king/consort was not only the kingship, and good sex, but the promise of apotheosis. Upon death, the rituals of sacrifice and lamentation assured that the king would ascend to the highest seat of heaven and be immortalized, where he would live among the gods. In contrast, mere mortals simply disappeared below the horizon into the Underworld upon their deaths.

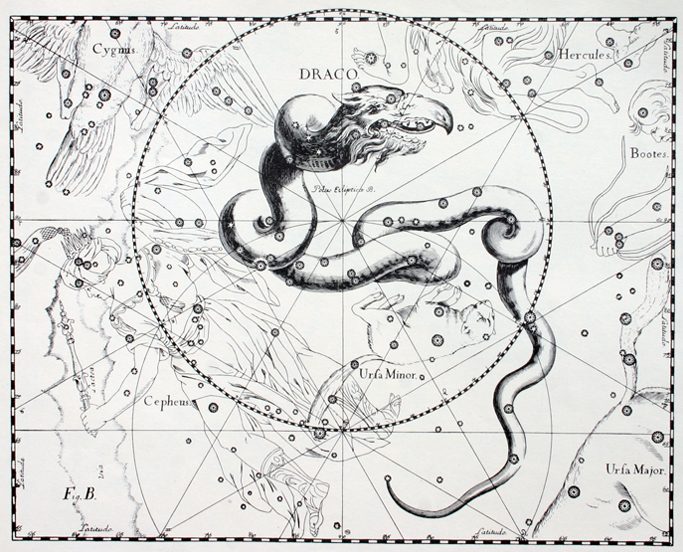

The process of hieros gamos sheds new light on why Ursa Major was once called the Wain or Wagon, accompanied by mourners (names of the stars on the tail of the bear) on their way to the highest seat of heaven. The flying horse Pegasus may also at one time have been the vehicle for the Goddess to accompany her consorts to their immortal resting place.